Choose a channel

Check out the different Progress in Mind content channels.

Progress in Mind

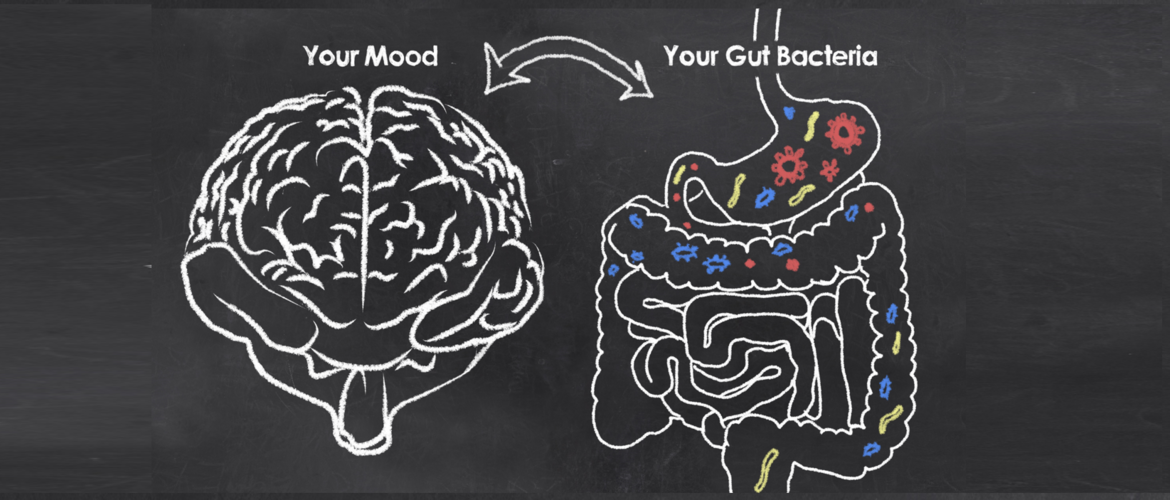

The role of the gut microbiome in a range of psychiatric disorders, including depression and anxiety, has become a major focus of scientific interest. The microbiome compromises 1.3 times as many cells as there are human cells in the body, and 500 times more genes. It provides nutrients for brain function and serves as an important interface between gut and brain. Recent studies provide evidence regarding underlying mechanisms and the potential therapeutic use of probiotics. This hot topic was unpacked by four experts during a CINP 2018 seminar.

All diseases begin in the gut

Dr Caitlin Cowan, from APC Microbiome Ireland, University College Cork, Ireland, introduced the session by demonstrating how the interaction between our gut and brain is firmly embedded in the English language. We use expressions such as ‘butterflies in my stomach’ and ‘gut-wrenching’, and even Hippocrates declared that ‘all diseases begin in the gut’. Gut health and psychiatric health go hand in hand, and up to 90% of patients with irritable bowel syndrome have at least one comorbid psychiatric illness.

The gut microbiome in people with mental disorders has a different profile from that in healthy controls

The gut microbiome in people with mental disorders has a different profile from that in healthy controls. That association is well established. But the microbiome may also have a more active causal role. ‘Transferring the blues’, Dr Cowan explained, has been demonstrated in rats, with depression-associated gut microbiota inducing neurobehavioural changes.

The ‘germ-free’ mouse provides evidence for early-life programming of the brain by commensal gut microbiota. In their absence, these animals demonstrate reduced levels of anxiety, impaired social behaviour, and an increased neuroendocrine response to stress.

Interestingly, many of these behaviours can be “normalised” by recolonization with normal gut flora around the time of weaning. Absence of microbiota in early life increases activity-related transcriptional pathways in the amygdala, a key brain region in processing and expression of anxiety and fear-related signals.1

A risk factor for development of psychiatric diseases later in life is early life stress, and the developing brain appears to be particularly susceptible during this period

A risk factor for development of psychiatric diseases later in life is early life stress, and the developing brain appears to be particularly susceptible during this period. Adverse influences early in development can lead to permanent changes in physiology and metabolism, which result in increased disease risk in adulthood.

Dr Cowan described their rat model of maternal-pup separation, resulting in anxiety, increased colonic transit and intestinal permeability. Usually memories acquired in infancy are rapidly forgotten in most species, including humans. In contrast, maternally separated rats demonstrated more adult-like fear retention on testing, and this could be reversed by administration of a probiotic.2

The effect of early life stress can be transferred across the generations, with offspring of rats exposed to maternal separation showing similar longer-lasting aversive associations, even though they never experience separation themselves. Interestingly, this can be reversed by giving probiotic supplements either to the infant rats, or, prophylactically, to their fathers (prior to mating).

No blanket mechanism to explain all the effects

Microbiota affect our behavior, Dr Cowan concluded, but as yet there is no blanket mechanism to explain all the effects. Proposed mechanisms include bacterial metabolites, immune signalling, tryptophan metabolism and neuronal signalling, and these ideas were further developed by subsequent speakers.

Dr Annamaria Cattaneo, from IRCCS San Giovanni di Dio and King’s College, London, proposed that inflammation has a central role behind many psychiatric as well as physical diseases. Usually there is an immunological equilibrium in the gut microbiota between commensals, symbionts with a regulatory role, and pathobionts with an inflammatory role; but this can be disturbed. Increased gut inflammation makes the gut more permeable, allowing bacterial components, bacterial metabolites, and a range of inflammatory mediators to be released into the systemic circulation, and subsequently reach the brain.

Dr Cattaneo described a small study in adults exposed to childhood trauma, demonstrating significant differences in gut microbiome composition compared to control subjects. Results mirrored those found in mouse studies of early life stress, using an isolation model during adolescence. Mice demonstrate impaired maturation of the microbiome profile, and male mice show lower basal levels of inflammatory cytokines and less effective immune response to acute stress. Many of these effects were long lasting.

Professor Rochellys Diaz Heijtz, from Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, discussed bacterial peptidoglycans (PGN) as novel signalling molecules from microbiota to the brain. Pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) of the innate immune system sense microbial molecules such as PGN during infection in order to initiate inflammatory responses. Importantly, ligands for PRRs are not exclusive to pathogens, and ligands from gut microbiota can also signal through PRRs to promote development of host tissues. Bacterial PGN ‘motifs’ translocate from the gut into the blood circulation and hence to the brain. This seems to be particularly important during specific windows of development in the early brain, when increased expression of PGN-sensing molecules (NOD-like receptor family, PGN recognition proteins, Toll-like receptor family) can be found.3

The tip of the iceberg for the role of gut microbiota

We are only touching the tip of the iceberg, Professor Diaz Heijtz said, in understanding the interaction between age, sex and brain circuits, and the part that gut microbiota may play. Expression of PGN-sensing molecules is sensitive to manipulations of the gut microbiota by germ-free conditions or antibiotics, and reduced levels were demonstrated in the germ-free mouse model. Interestingly, expression of PGN-sensing molecules shows sex- and brain regional-differences; and absence of PGN-recognition protein 2 (Pglyrp2) in a knockout mouse model led to sex-dependent changes in social behaviors.3

Pglyrp2 also seems to be important later in life. Elderly knockout mice show altered levels of anxiety-like behaviour and altered expression of neuronal proteins such as alpha-synuclein in certain brain regions, with significant sex differences.3

Professor Premysl Bercik, from Division of Gastroenterology, McMaster University,Ontario, Canada, concluded the symposia by discussing the potential functional role of microbiota in co-morbid anxiety associated with irritable bowel syndrome and generalized anxiety disorder.

Faecal transplants from irritable bowel syndrome patients induce anxiety-like behaviour, innate immune activation, altered serum metabolomic profile, and faster gastrointestinal transit in a germ-free mouse model.4 A similar role for microbiota has been proposed for the primary psychiatric condition generalized anxiety disorder. Innate immunity is upregulated in these patients, and immune activation can be transferred to mice through a fecal microbial transplant from a patient with generalized anxiety disorder, with associated anxiety-like behaviour and reduced levels of hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).

Probiotics can improve depression and quality of life

Probiotics can reduce GI symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, but less is known about effects on psychiatric co-morbidities. A recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 44 adults with irritable bowel syndrome and mild-moderate anxiety and/or depression showed the probiotic Bifidobacterium longum can improve depression scores and increase quality of life, with reduced brain limbic system activation and altered urinary metabolites involved in catecholamine metabolism.5

Results are supported by studies in mice, looking at infection with the non-invasive parasite Trichuris muris. Animals demonstrate anxiety-like behaviour, reduced hippocampal BDNF mRNA, colonic inflammation, and increased pro-inflammatory cytokines. Administration of B.longum normalized the effects on behavior and hippocampal BDNF mRNA, without altering cytokine levels.